Malaria

- Kanav Dani

- Sep 18, 2022

- 2 min read

Malaria served as the reason for 627,000 deaths worldwide in 2020. 93% of these deaths

occurred in sub-Saharan African nations. Furthermore, 80% of the malarial deaths in Africa

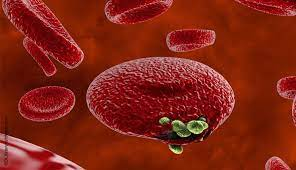

occurred in children under 5 years of age. Caused by unicellular parasites, malaria is primarily

transmitted through mosquito bites. When a malaria-infected mosquito bites a human, the

malarial parasites enter the host’s bloodstream and eventually infect their liver (first stage). The

parasites remain in the liver, multiplying for 7-10 days before they enter the main bloodstream

and begin spreading throughout the body of the host, invading red blood cells. The parasites will

then multiply inside of the red blood cells, causing them to burst. At this stage, the infected red

blood cells make the host symptomatic.

Till date, the only treatments for malaria include anti-malarial drugs or insecticides.

However, the recent rise of mosquitoes immune to insecticides and malarial parasites immune

to antimalarial drugs has increased the need for an effective vaccine to use against the

sickness. One of many challenges to the development of a reliable vaccine is the complexity of

genomes that comprise the sickness. For example, the genome of P. falciparum (a malarial

parasite) is much larger and more complex than entire viruses, and consists of over 5,000

genes. Furthermore, the life cycle of this parasite, with its multiple stages, has made it difficult to

select an appropriate protein to target in vaccine development.

However, among the development of several vaccine candidates, RTS, S AS01,

otherwise known as Mosquirix, has shown the most promise. It targets the life stages of the

Plasmodium parasite that occur before the invasion and infection of red blood cells. The

circumsporozoite protein is a major protein expressed on the side of the parasite, and the

Mosquirix vaccine trains the body to elicit an immune response against this protein. However,

many problems lied within the vaccine, causing issues with its efficiency, leading researchers to

develop a new vaccine called R21. In clinical trials with 450 patients, the low adjuvant doses of

R21 have had success rates of 71%, with the high adjuvant doses having success rates of 80%.

Malaria has caused much damage to many people and their families, but we may be gradually

advancing to a solution that puts an end to this sickness.

Comments